May through November is prime-time tick activity here in southeast Wisconsin. Just the mention of these creepy-crawlies tends to stir up the heebie-jeebies.

But how much do we actually know about them? How can we coexist with ticks in a way we can feel confident and worry-free to enjoy our outdoor activities with our families and pets? Can we identify ticks by species and different life stages so we understand legitimate risks?

Let’s free ourselves from worry and disinformation by educating ourselves and being properly prepared…read on to find out more!

BASIC TICK EDUCATION—A BRIEF ENTOMOLOGY LESSON

What are they?

Ticks are external parasitic arachnids (8-legged). Specifically, the class Arachnida—yes, along with spiders and scorpions! They specifically are classified in the order of Acarina which indicates their non-segmented bodies in comparison to other arachnids. They are in the superorder of Parasitiformes, which consists of mites; and the suborder of Ixodida, representing what are called “hard ticks”, which are what we encounter here in Wisconsin.

What do they eat?

Just like a cat is an obligate carnivore (derives its nutrition and best survives on meat), ticks are obligate hematophages, meaning they rely solely on blood to progress through their life stages. When a tick attaches to a host to feed, this is called a blood meal.

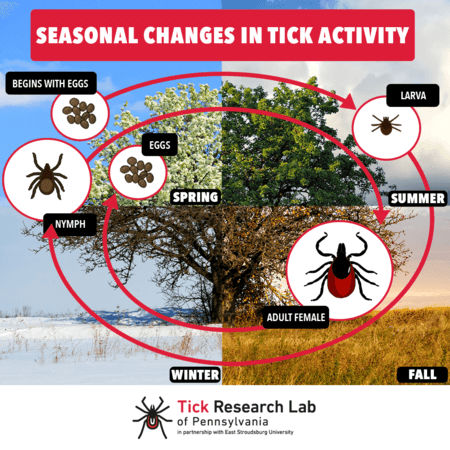

What are their life stages?

The life stages of a tick are egg, larva, nymph, adult. All life stages of a tick need a host and blood meal to survive. Larvae are 6-legged and hatch in early summer. They typically choose small mammals like rodents or squirrels as their first host. The White-Footed Mouse is a common choice and plentiful here in southern Wisconsin, and also known to sometimes carry the bacterium that causes Lyme Disease. Once the larvae have fed for several days, they will detach and continue their development through fall and winter, at some point molting into tiny non-gender nymphs with 8 legs, about the size of a poppy seed.

Spring is the most active time of year for most species of ticks, as now the nymphs are “questing” for larger hosts such as raccoons, dogs, and even humans. Questing is when a tick climbs up a large blade of grass or other foliage and waits with its front legs extended to grab onto a passerby. After its next blood meal, a nymph will detach and remain hidden away until its next molting in the fall where it becomes a male or female adult.

Female adults will seek out one last blood meal in the fall. She will engorge herself, detach, mate (if a male didn’t find her on a host) and then rest in leaf litter or undergrowth until spring when she lays her eggs on the ground, many times nearby where she detached from her last host. Ticks do not have nests, per se, but rarely under some ground vegetation you may site a small cluster of tick eggs (smaller than a quarter) that looks akin to tiny caviar. The cycle then begins again, with the larvae hatching in the early summer.

Important reminders

Ticks tend to be commonly found in areas with tall grasses, as this affords them a way to crawl up and board their hosts as they brush by (questing). They do not live in trees. They thrive best in warm, humid weather; tall grasses also provide needed humidity. Droughts will typically reduce tick populations.

In addition, ticks do not hibernate in winter nor does the cold weather kill them off. Their body processes slow down until the environmental conditions are conducive to their activity, usually above freezing. This explains why during a mild spell in winter you may find the random tick that hitched a ride on your dog!

THE MOST COMMON WISCONSIN TICKS

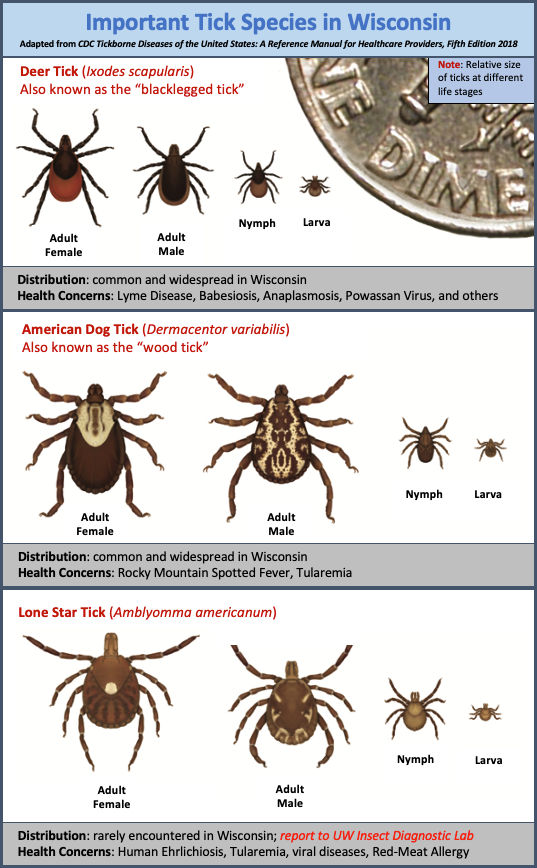

According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, there are 16 species of ticks known in the state of Wisconsin. Most of these species do not feed on humans.

However, there are two species that most of us will encounter: the Deer Tick (aka Blacklegged Tick, Ixodes scapularis) and the Wood Tick (aka American Dog Tick, Dermacentor variabilis).

Special mention is the Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum), which is rarely sighted but most reports come from the southern half of the state.

Deer Tick, sometimes Bear Tick (aka Blacklegged Tick, Ixodes scapularis)

The Deer Tick has become best known for being a possible carrier of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi which causes Lyme Disease. Originally it was thought that the Deer Tick larvae were hatched free of disease, but new studies show it may be possible for the females to pass on pathogens to her eggs. However, research is still claiming that nymphal Deer Ticks are the main transmitter.

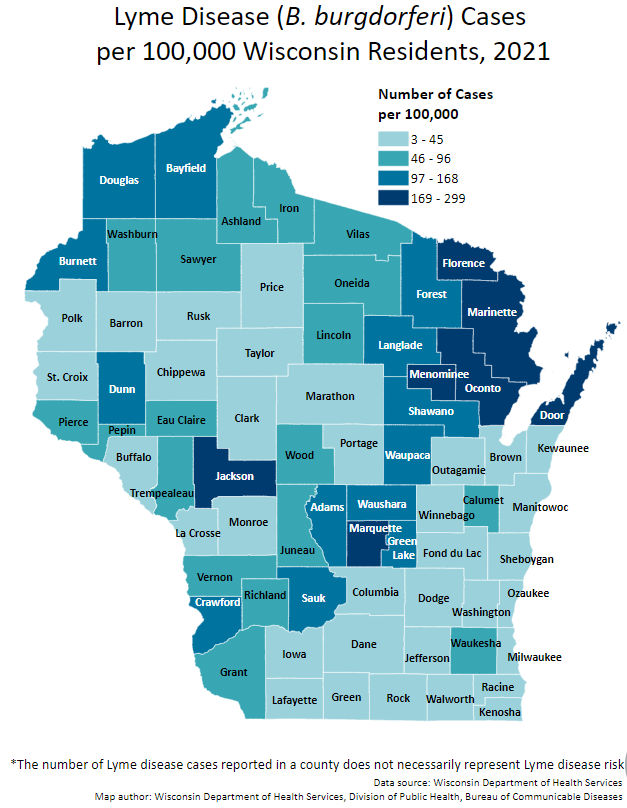

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services reported in 2021 that nearly all of southeast Wisconsin had the lowest number of cases per 100,000 residents, with the exception of Waukesha county, which had 46-96 cases/100,000. The heaviest number of cases were primarily in the northeastern counties. (See: Lyme Disease, Wisconsin Data. The number of Lyme disease cases reported does not necessarily represent risk.)

Of note for the Deer Tick:

The Deer Tick nymph’s peak feeding activity in Wisconsin is from May-July, so this is when we should be most vigilant about protection since they are extremely small and harder to detect.

Wood Tick (aka American Dog Tick, Dermacentor variabilis)

The Wood Tick is not known to be a vector of disease in Wisconsin, although in other parts of the country it is known to carry pathogens that cause Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Tularemia (aka Rabbit Fever). As its name suggests, the “American Dog Tick” is commonly found on small animals like dogs and cats.

Of note for the Wood Tick:

Both its larva and nymph stages target small mammals as their hosts. Humans and larger pets and animals usually only encounter the adult phase Wood Tick. Its peak activity in the midwestern US occurs in May and June and then sometimes again in August and September.

THE BEST WAYS TO PREVENT TICK-BORNE DISEASES

Well, of course never going outside and not having pets might prove to be the best way—but who is going to do that when we have such a beautiful state to explore and lots of dog walkies to give?

The prevention of giving these blood-sucking hitchhikers a ride is the first layer of protection. Depending on the weather and excursion, you can protect yourself by wearing long pants, tucking them into your socks or inside your boots and using your chosen repellant mostly on that lower half of your body where they will tend to jump on. For your dog, applying repellant to their legs, bellies, chest will help the most in repelling ticks, as well as using any other products you deem fit for your furry family member. Try to avoid hiking through those tall grasses!

Do a quick full-body tick-check on yourself and your pets after each outdoor excursion. Using a lint roller on your clothing (and even bare skin) or dogs before coming inside is an easy way to remove stragglers!

When properly removing any attached ticks within 24 hours, you greatly reduce the possibility of any bacterium transmission. It usually takes 36 hours or more for the pathogen to be transmitted via the feeding tick. (See Lyme Disease transmission information at cdc.gov.) However, studies overall do not show conclusive results, so doing the tick-checks ASAP is always the best idea.

HELP YOURSELF & GET INVOLVED: CHECK OUT THE TICK APP

A team comprised of researchers from researchers from Columbia University, Michigan State University, the University of Illinois and the University of Wisconsin-Madison created The Tick App to make identifying and reporting ticks fast and easy! It’s available for both Android and Apple products.

This page on The Tick App website is an excellent resource for identifying Wisconsin’s most common ticks!

Their mission with The Tick App is to collect information from the public via this smart phone application to study tick exposure and the risk of Lyme Disease.

You can find out more at The Tick App website and you can follow them on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

Sources:

- Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Entomology at the University of Kentucky

- The University of Rhode Island TickEncounter

- Iowa State University Extension and Outreach

- University of Florida Entomology and Nematology

- Wisconsin Department of Health Service

- A Systems Approach to Understanding Tick-Borne Diseases: People, Animals and Ecosystems

- Transmission of the relapsing fever spirochete, Borrelia miyamotoi, by single transovarially-infected larval Ixodes scapularis ticks

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- LymeDisease.org

- Encyclopedia Britannica

.png)